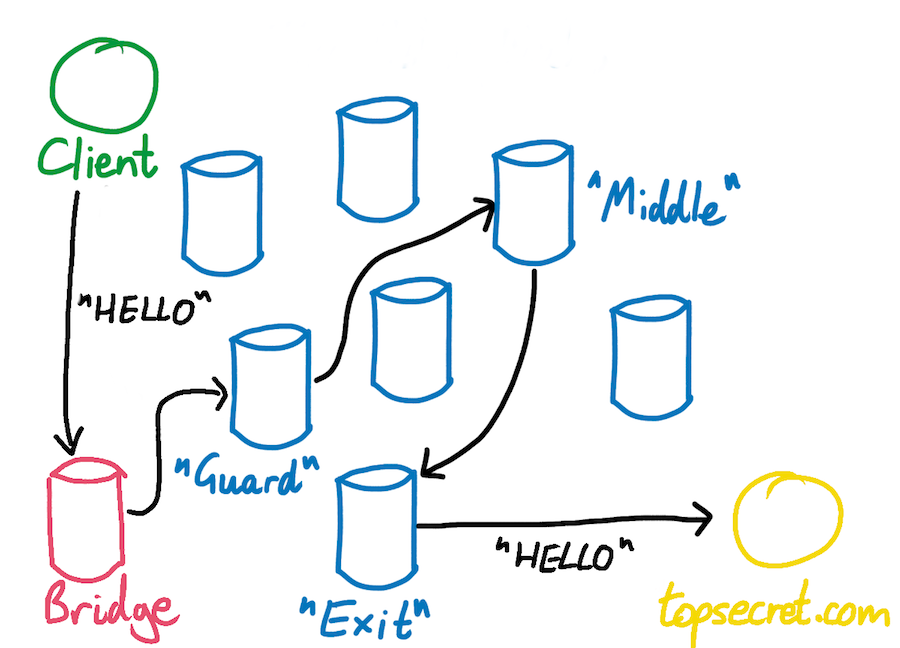

Governments across the world continue to block & restrict access to the uncensored Internet, with many of them blocking & restricting the use of the Tor network as a result. Over a year ago, we launched Operation Envoy, an effort to help defeat those Internet censors. Operation Envoy originally helped with our vast deployment of Tor bridges & snowflake proxies, which help to pass messages (IP packets) back and forth from users and the Tor network. These messengers, or envoys as we call them, allow people to access the uncensored Internet and disguise their use of Tor from prying eyes.

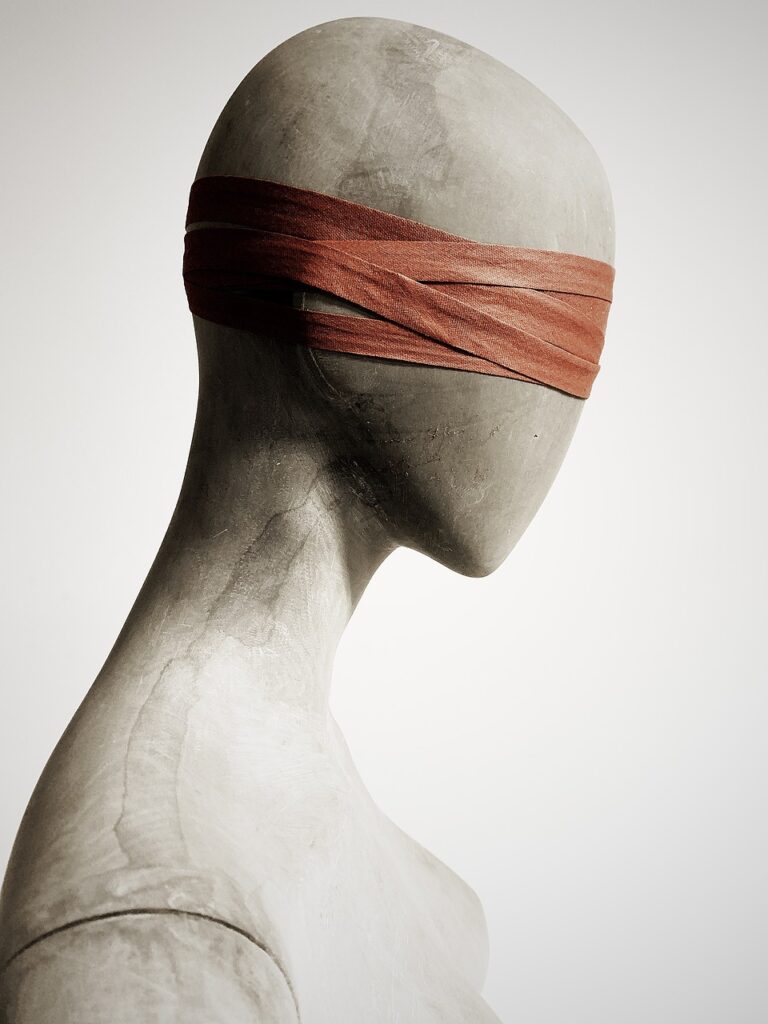

Obfuscation of the messages that our envoys carry to and from uncensored networks are incredibly important in keeping users safe. In many countries, it’s outright illegal or highly discouraged to use these technologies to bypass Internet censorship. Some people could be in real danger if their government found out that they are circumventing Internet censorship. This is morally wrong, and with governments across the world continuing to abuse their powers and limit the free flow of information, we’ll continue fighting against it.

It’s no secret that people in countries such as Russia and Iran (& some in China) heavily depend on censorship-resistant bridge & proxy technologies according to Tor’s metrics. To help people in even more countries, and in more ways, we want to expand our vision of what Operation Envoy is.

Redefining what an envoy is

After we originally launched Operation Envoy, we launched FreeSocks – a service that provides free, open & uncensored Outline (Shadowsocks) proxies to people in countries experiencing a high level of Internet censorship. We also launched Unredacted Proxies, which allow people to connect to messaging services such as Signal and Telegram, without exposing the fact to their ISP or government.

Today, we are redefining what an envoy is to us – it’s any of our services that pass messages (IP packets or TLS wrapped application layer data) back and forth between a user and the uncensored Internet. These services should all obfuscate those messages in a way where anyone monitoring a user’s Internet usage would not be able to tell what those messages might contain. In other words, they all should use an obfuscated protocol of some kind.

Operation Envoy now includes:

- FreeSocks (uses Outline, which is based on Shadowsocks)

- Unredacted Proxies (uses Signal’s TLS proxy & Telegram’s MTProto proxy)

- Unredacted Tor bridges & snowflake proxies (uses obfs4 or snowflake)

These services currently all fall under our Censorship Evasion (CE) services.

Operation Envoy does not include:

- Unredacted Tor exit relays (these are the last hop, and not directly related to what Operation Envoy is about)

- Any of our Secure Infrastructure (SI) services (such as Unredacted Matrix & XMPP.is)

Operation Envoy metrics

Operation Envoy started with 34 CPU cores and 58 GiB of RAM, deployed all over the world. We’ve since scaled the operation, and we currently have 61 CPU cores (nearly double), and 70 GiB of RAM dedicated to delivering uncensored access to the Internet (excluding our Tor exit relays). We’re working to expand that on a regular basis, and continue growing the number of envoys at our disposal.

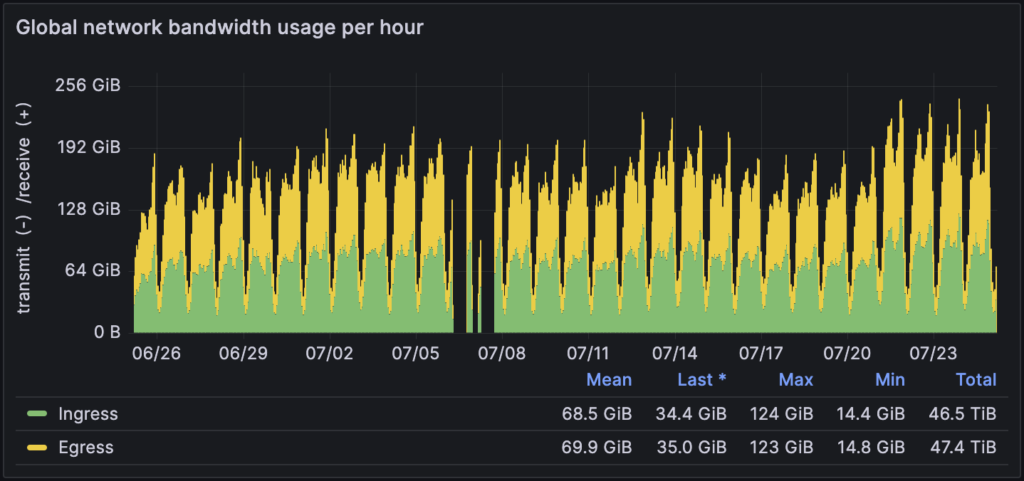

To collect anonymized metrics on all of ours envoys, we created a new Grafana dashboard which details the hourly bandwidth usage of all envoys combined. Over the last 30 days (at the time of writing) we pushed over 152 TiB of bandwidth across all of our envoys. That’s a lot of data!

We need your help!

Unredacted Inc is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, and we directly depend on generous donors like you to fund our operations. If you like what we do, and want to support our mission, please consider donating. We couldn’t fund Operation Envoy, and many of our services without your help.

As a special promotion, if you donate $10 USD/mo (or more) to us on a recurring basis after reading this blog post, we’ll deploy an envoy of your choice in honor of your generosity. If you do this, please contact us afterwards and we’ll coordinate with you.

Thank you!